- Home

- C. S. Thompson

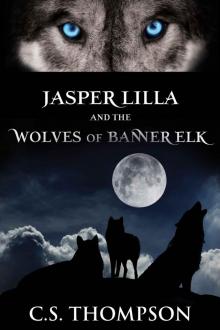

Jasper Lilla and The Wolves of Banner Elk Page 3

Jasper Lilla and The Wolves of Banner Elk Read online

Page 3

“Wolves,” I said bluntly.

She stared at me. “Wolves,” she repeated. “What do you mean, ‘wolves’?”

“A pack of wolves showed up. The last time I saw those dogs they were running from the wolves.”

“Wolves,” she repeated again.

“You don’t believe me?” I asked.

She exhaled loudly, and her face seemed to relax. “I believe you,” she said in a whine, “but I don’t know what to think either.”

I still hadn’t told her everything, but it wasn’t time.

She leaned close enough to me for our shoulders to touch and focused on the empty seat across from us.

“You know,” she sighed, “there aren’t supposed to be any wolves around here.”

“I know.”

Looking back at me she asked, “What did your mom say?”

“I didn’t tell her.”

Her eyebrows flinched together.

“You’re the only person I’ve told.”

“Why didn’t you tell your mom?”

“There’s more,” I said.

She pulled her head back. “You’re kidding.”

I shook my head no.

“Tigers?” she guessed.

I pulled the wolf’s tooth up out of my shirt by the strap and dangled it away from my chest.

Riley looked at the tooth, and then she looked back at me.

“At one point I fell off that ledge last night,” I told her.

She took hold of my left hand with both of hers.

“I thought I was going to die.”

She squeezed my hand.

“Those dogs were ready to kill me, but when I fell I grabbed this.” I shook the wolf’s tooth.

She let go of my hand.

“That sounds nuts, doesn’t it?” I asked.

“That depends,” she said, taking hold of my hand again. “Are you telling me it was an incredible coincidence? Or are you telling me you made it happen with your necklace?”

Six

Maggie

I didn’t answer. Apparently I did think it was the necklace that made it happen, but I didn’t think I thought it until I said it out loud. “I don’t know what I think,” I said. “But I think I’ll keep it to myself until I get it more clear in my head.”

Riley gave me one of those smiles that teetered between pride and pity, so I couldn’t tell if she agreed with me or felt sorry for my confusion.

I tucked the necklace back inside my shirt.

“You know,” she said, “I’ve been to your house, but you’ve never taken me to see the alpaca.”

She might have just been changing the subject to make me feel better, but I didn’t care. It worked.

* * *

Riley went home with me after school the next day. The bus let us off at the bottom of the driveway, which was about the length of a football field and ran alongside what we called the front pen. We used to keep some alpaca in the front pen, but sightseers kept coming by and feeding them leftovers from Happy Meals and doughnuts, so now it’s just our front yard.

About halfway up the drive Riley said, “Cool.” She was looking at our house.

“Thanks,” I told her. Our house is kind of cool. Aunt Maggie says we don’t appreciate where we live, but we will when we leave. She’s sort of right. I don’t generally think about it unless someone else is looking at it the way Riley did right then.

Our house sits on a hill at the top of the front pen. It’s mostly made of large granite stones with white trim. It was modeled after a log hunting lodge my parents went to in Wyoming on their honeymoon. The windows in the front make it look like one story, but the windows are all huge, as are the pillars on either side of the stone stairs leading to the front door. The roof slants back far enough to accommodate two stories on the back side of the house. Truthfully, I hardly ever notice the front. We come and go through the kitchen, which is in the back of the house. The kids’ bedrooms and a TV/game room were upstairs over the kitchen, a laundry room, Aunt Maggie’s room, and a guest room. Mom’s bedroom, an entry, a great room, and a library were along the front.

“This way,” I told Riley, directing her around to the back of the house rather than the front.

Behind the house there are several outbuildings. The first one is a guest house remodeled to be a studio for Carol when and if she visits. Then there are two barns: a big one we use for shearing in the spring and a smaller one connected to the pen just behind the first outbuilding. Two more pens, each with a small shelter, came next, and the woods and then the mountains after them.

“Gorgeous,” said Riley, stopping at the corner of the house. “As many times as I’ve been here I’ve never seen the view from the back.” She smiled. “If I lived here I’d want to put a picnic table out here and eat every meal looking out at this.”

I wanted to agree with her, but that would have sounded silly, so I said, “We like it here.” I wish I had told her I’d put a picnic table anywhere she wanted.

“How’s it going?” I asked Aunt Maggie as Riley and I approached the small pen where she was standing next to a black alpaca I didn’t recognize.

* * *

Aunt Maggie is our aunt. She’s not our aunt by blood, but she’s my aunt all right. She’s been with our family as long as I can remember, but Carol told me that she came after our dad died. Maggie runs the farm pretty much by herself. We keep about fifty alpaca, which may be a small herd, but it’s still too big for one person to handle alone—unless you’re Aunt Maggie, that is.

When Linus played for the Baltimore Ravens he told me there was no one on that team that she couldn’t handle. Sometimes I think that was an exaggeration. Sometimes I don’t. I know this: I was never afraid of anything if she was around. While kids in other families played who-can-stare-at-the-sun-the-longest, we played who-can-stare-at-Aunt-Maggie-the-longest. Carol lasted three minutes once. No one ever beat Maggie, though. How could anyone beat her? Staring was what she did. Staring is what she always did.

* * *

“She is new,” answered Aunt Maggie, looking squarely at Riley. “She is new, too.”

“Do you remember Riley?” I asked.

“Welcome, Riley,” said Aunt Maggie. She waved us in. “I am Aunt Maggie. And this one is Beauty. She just came to us this afternoon. You can help us get her used to people.”

I opened the gate.

“She won’t hurt you,” Aunt Maggie assured Riley, “but watch your feet. She might step on you.”

Once we were both inside the pen Aunt Maggie came close enough to take Riley’s hand. “What a pretty child you are.”

Riley said, “Thank you.” While they still held each other’s hand, Beauty nudged her head up under Riley’s elbow. “Oh,” said Riley with a start.

“You must have the magic touch with this one,” said Aunt Maggie. “She’s not warmed up to me like that.”

Riley tried to pat Beauty’s head, but the alpaca ducked under her hand.

“She’s a little skittish,” explained Aunt Maggie. “She came to us from a much larger alpaca farm, so she didn’t get the same kind of human attention my girls get. Try scratching her around her jaw.”

“Like a dog,” said Riley as she followed the suggestion.

“Yes, she said, “like a dog. Alpaca are very much like dogs. If they are kept chained in the yard they will be very different than if they are allowed on your couch.” She pointed at Riley’s hand as she stroked up and down Beauty’s neck. The more Riley stroked, the more Beauty seemed to lean into her. “You found the spot,” chuckled Aunt Maggie.

Alpacas hum. At least that’s what Mom calls it. To me it sounds like a homemade kazoo a kid would make with a comb and a piece of paper. That’s the sound Beauty made as Riley rubbed her neck. Apparently Riley had never heard it before, because she immediately looked around to see where the sound was coming from.

“It’s Beauty, darling,” said Aunt Maggie. “She’s talking to you.”

“Really,

” said Riley, moving closer to Beauty’s face. The humming stopped.

Leaning farther down, Riley ran her hand around to Beauty’s belly, which made Beauty jump back.

“I’m sorry,” pleaded Riley to Aunt Maggie. “I thought she’d like that. My dog loves that.”

“It’s okay. She’ll be fine,” said Aunt Maggie. “The belly is very sensitive for the alpaca. That is where a coyote will bite them.”

“Coyotes,” repeated Riley. “Are there coyotes here?”

“There are,” I told her. “Aunt Maggie killed one with her walking stick a couple of years ago.”

Riley surveyed Aunt Maggie more closely. Aunt Maggie is short, but she’s built like a fire hydrant. Her dark ebony skin makes it difficult to guess her age. It also makes it obvious she not my biological aunt. You don’t tend to notice any of her features when she looks at you because if she catches you in her eyes, her eyes will be all you see. If you didn’t know her, you’d find the story of her killing a coyote with a walking stick impossible to believe, but if you’d ever been caught in her stare you’d have no problem at all believing it.

“The coyotes moved in when the red wolves were nearly extinct. Now that the red wolves are coming back, the coyotes will get more scarce,” explained Aunt Maggie as she soothed Beauty.

“Aunt Maggie spread the coyote’s blood across the back of our property,” I bragged.

“It’s a trick from the old country,” Aunt Maggie said, the way another woman might have explained her secret for flaky pie crust.

“The red wolves are coming back?” asked Riley.

“They were nearly extinct, but they were reintroduced to the wild in the Smokies not too long ago,” answered Maggie.

“Were you involved with that?”

“Not me,” said Aunt Maggie, “but the mother was.” That’s what Aunt Maggie called my mom: “the mother.”

Seven

Putting the Necklace Away

It was two years ago when Riley and I had that conversation about the wolves and the Dobermans. Other than Riley informing me that my cell phone was not in the Lion Pharmaceuticals lost and found, neither she nor I ever brought it up again. I put Linus’swolf’s-tooth necklace back in its leather pouch and hid it under the collection ofX-MenandAvenger comics I keep in a toy box that Linus made out of an old ammo trunk for me one Christmas.

As best we could, life went back to normal. The first Christmas without Linus was horrible. Mom made us do everything we always did during Christmas, but we were all faking it and we all knew it. Mom went back to her writing and Carol went back to school and Aunt Maggie went on being Aunt Maggie.

One of the biggest things that happened to me was that I entered Watauga High School the next fall and that meant I got Aunt Maggie’s be-true-to-yourself lesson before school started. Her lesson was more of a riddle than a lecture. She’d ask, “What do you call a person who always follows another?” The answer she was looking for was, “Lost.”

When my turn came, the answer she got from me was, “I’m not lost. I’m Jasper Lilla.” It was an ironic riddle considering that I’ve never had an identity of my own. My father died before I was born. He was a professor of anthropology at Appalachian State, so if I ever go there I’ll be Jackson Lilla’s son. More often than not though, I’m Vernalisa’s son. I’m the youngest son of famous author Vernalisa Vanderguard.

Eight

Vernalisa Vanderguard

I didn’t know my mom was famous until I was old enough to notice she had a last name different from the rest of the family. I knew she went away a lot on what she called “business.” She was either writing a book or promoting a book, but I didn’t know about that when I was little. I just knew she was gone. Then once, when I was four, I got to go with her to a book signing in New York. I don’t know if we were in a library or a bookstore or what, but we were in a big room surrounded by bookshelves and murals of cartoons. She sat on the floor and read one of her stories to a whole bunch of kids. The kids were mostly older than me. At the time they seemed loud and pushy to me, but maybe they were just older and bigger. They were definitely more used to being in a crowd. I grew up on an alpaca farm. A crowd like that was overwhelming to me back then. It might still be. I remember all the parents standing along the walls taking pictures of us. I didn’t like it. I didn’t like the crowd, the attention, or the flashing of the cameras. It all scared me.

I had never heard her read before. For me, she just told stories. I didn’t know she wrote them down for others. At home she’d tell me stories while we walked or when she cooked or when she put me to bed. I’d heard the story she was reading. It was a story about a misunderstood porcupine. When we first sat down I was sitting on the floor next to her, but I climbed into her lap when the kids kept getting closer and closer. She must have known how frightened I was, because at one point she whispered, “Hold my neck.” When I heard that I stood up in her lap, turned around, and buried my face in her thick black hair. That was also when I discovered how much her hair smelled like honeysuckle.

Now that I’m older I think the thing that bothered me the most about that day was her relationship with all those strangers. She was supposed to be my mom, not their mom. They—every one of those kids, those parents, those strangers—acted like she belonged to them. I didn’t want her to belong to anyone else. I wanted her to belong to me, just me. I wondered how could she be there for me when I needed her if she belonged to so many of them.

It was after that that she told me about putting her stories into her books.

“All your stories?” I remember asking.

“Why not?” she replied.

I almost cried. “Because those stories are mine,” I told her.

She laughed. It wasn’t a big laugh, but it was a laugh. “Those stories aren’t even mine,” she told me. Then she stroked my cheek with the back of her hand. “But me,” she said, “I’m yours.” Then, as she kissed my forehead, I smelled honeysuckle again.

* * *

It seems funny to me now that I’m older to have felt that way then, but I did. Now I’m proud of her. She’s brought a lot of joy to a lot of children. I’m proud of what she has accomplished. Her being a famous author is kind of cool. It’s a bit of a pain that everyone I know knew my mother first, but that goes away quickly when she’s around. She doesn’t ever act like how I envision a famous author would act. She never, ever acts like she is the important one when she is with anyone else. She’ll sign a book and say “Thank you” when she is praised, but every conversation with her ends up being about whomever she is talking to. She is genuinely interested in everything and everyone, and she remembers everything and everyone. So it only takes meeting my mom once, and she stops being this famous author you read as a kid and becomes what one of my friends called her: “the mother to us all.”

My sister, Carol, once told me that her friends have a different name for our mother. Carol and her friends are retro-hippie types. They’re into sixties’ music, sustainable agriculture, and yoga. Carol’s friends call her an “earth mother.”

That’s my mom. In a way she belongs to everyone who’s ever read her stories. In another way she belongs to everyone who has ever talked to her. But in every way she is my mom. And although lots of people know lots about her, I know something about her no one else knows. Honeysuckle smells like my mom.

Nine

My Brother Linus

Aunt Maggie’s be-true-to-yourself riddle became even more ironic once I began attending Watauga High School. I was still Vernalisa’s son, but often I was Linus’s little brother.

Now, “Linus” wasn’t his real name. It was the name Coach Pinkus, the Watauga High School head football coach, gave him. Like Linus from the Peanuts cartoon, Linus had a favorite blanket he was attached to. To wean him from the blanket, Mom cut it in half every time she washed it. Eventually it was just a sliver, and he hid it from her, although I’ll bet she knew all along. He hid it so well that he forgot about

it until he was a sophomore in high school. He found it and used it as a headband underneath his football helmet before the third game of the season. He was a backup wide receiver and the only sophomore on the varsity team, but during that third game the senior starter dropped a wide-open pass in the end zone and Linus got his chance to play. He scored two touchdowns in the second half. From that day on, he never played without his blankie headband. A year later he was a junior, and our sister, Carol, was a freshman. For her freshman English class Carol wrote an essay about Linus’s headband. The story spread through the school so fast that it reached the coaches’ office that same afternoon. Carol got an A, and Linus, whose real name was Thomas, got a new name that stuck with him ever since.

Linus was a football star, and that got him a full scholarship to Wake Forest University, where he played wide receiver and returned punts. He was an academic All-American his junior and senior years. No NFL teams drafted him, but the Baltimore Ravens signed him as a walk-on. He had great hands, ran great routes, and could catch the ball in a crowd, but he was so slow that he could only beat two of the offensive lineman and none of the defensive lineman in the forty-yard dash. He made it through the exhibition season but got cut before the regular season began. I’ve got a picture of him catching a pass against the Jets on my wall right next to a picture of him in his uniform.

He enlisted right after the Ravens cut him. He had studied marketing in college and could have gone to work for our mom, but that’s not what he did. He told her there’d be time for that later. He told me he hoped the army would make him faster.

Around Boone, at least around Watauga High School, Linus was almost as famous as Mom. Maybe he just seemed more famous because more people asked if I was Linus’s brother than asked me if I was Vernalisa Vanderguard’s son. Because of football, Linus was famous around here before he was a hero, but once he was a hero, his fame spread even more. They held a service of remembrance for him at the high school auditorium, and it was packed. Coach Pinkus tried to say something but couldn’t.

Jasper Lilla and The Wolves of Banner Elk

Jasper Lilla and The Wolves of Banner Elk